Exhibition review at Contrast Gallery/Pearl Lam Gallery Shanghai China

Ann Brodie Shanghai Talk 2008

I have to admit that for a large portion of my interview with British artist Simon Casson. I’m completely baffled. He rattles off endless lists of obscure artists – expected and even more obscure mathematical theories – unexpected – that apparently influence the design and layout of his paintings. “I just picked up on these things when I was studying…you build up a vocabulary of what’s around you, what you hear and see,” Casson says.

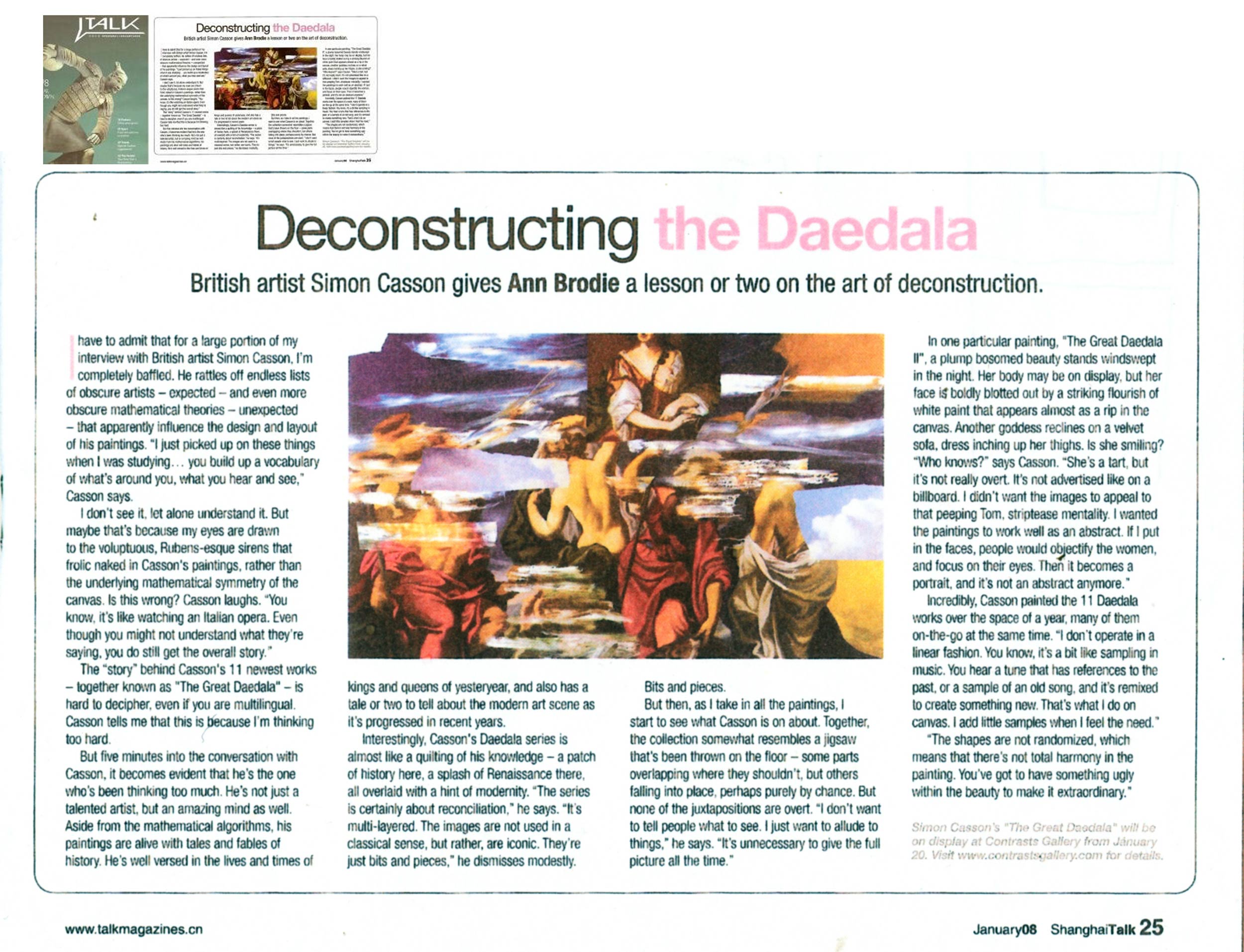

I don’t see it, let alone understand it. But maybe that’s because my eyes are drawn to the voluptuous, Rubens-esque sirens that frolic naked in Casson’s paintings, rather than the underlying mathematical symmetry of the canvas. Is this wrong ? Casson laughs. “You know, its like watching an Italian opera. Even though you might not understand what they’re saying, you do still get the overall story.”

The “story” behind Casson’s 11 newest works – together known as “The Great Daedala” – is hard to decipher, even if you are multilingual. Casson tells me that this is because I’m thinking too hard.

But five minutes into the conversation with Casson, it becomes evident that he’s the one who’s been thinking too much. He’s not just a talented artist, but an amazing mind as well. Aside from the mathematical algorithms, his paintings are alive with tales and fables of history. He’s well versed in the lives and times of king and queens of yesteryear, and also has a tale or two to tell about the modern art scene as it’s progressed in recent years.

Interestingly, Casson’s Daedala series is almost like a quilting of his knowledge – a patch of history there, a splash of Renaissance there, all overlaid with a hint of modernity. “The series is certainly about reconciliation”, he says.”It’s multi-layered. The images are not used in a classical sense, but rather, are iconic. They’re just bits and pieces.” he dismisses modestly.

Bits and pieces.

But then, as I take in all the paintings, I start to see what Casson is on about. Together, the collection somewhat resembles a jigsaw that’s been thrown on the floor – some parts overlapping where they shouldn’t, but others falling into place, perhaps purely by chance. But none of the juxtapositions are overt.” I don’t want to tell people what to see. I just want t allude to things”, he say. “it’s unnecessary to give the full picture all the time”.

In one particular painting. “the Great Daedala II”, a plump bosomed beauty stands windswept in the night. Her body may be on display, but her face is boldly blotted out by a striking flourish of white paint that appears almost as a rip in the canvas. Another goddess reclines on a velvet sofa, dress inching up her thighs. Is she smiling? “who knows?” says Casson. “She’s a tart, but it’s not really overt. It’s not advertised like on a billboard. I didn’t want the images to appeal to that peeping Tom, striptease mentality. I wanted the paintings to work well as an abstract. If I put in the faces, people would objectify the women, and focus on their eyes. Then it becomes a portrait, and it’s not an abstract any more.”

Incredibly, Casson painted the 11 Daedala works over the space of a year, many of them on-the- go at the same time. “I don’t operate in a linear fashion. You know, it’s a bit like sampling in music. You hear a tune that has references to the past, or a sample of an old song, and it’s remixed to create something new. Thats what I do on canvas. I add little samples when I feel the need”.

“The shapes are not randomized, which means that there’s not total harmony in the painting. You’ve got to have something ugly within the beauty to make it extraordinary.”